The time has come! We enthusiastically welcome you to something we have been anticipating for some time … the launch for The Literacy Bug. So … please … say “HELLO” to Ludwig, a little bug who always has his head in a book.

Even though this launch comes with a fair amount of celebration, I must admit that it also comes with a teeny, tiny bit of sadness … not much … just a small morsel of it. I am compelled to remind myself that “we are NOT saying goodbye to Wittgenstein on Literacy or Wittgenstein on Learning.” The core spirit of the old name(s) will remain. It is not possible to severe the site’s deep ties to the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. After all, Wittgenstein was deeply fascinated by the diverse ways that language and literacy are used between people in the general course of living, imagining, conceptualising, doing, knowing, speculating, calculating, relating, etc. Perhaps the change of name is just a clever ploy and the discussion will go on as usual. To a certain extent, I think it will.

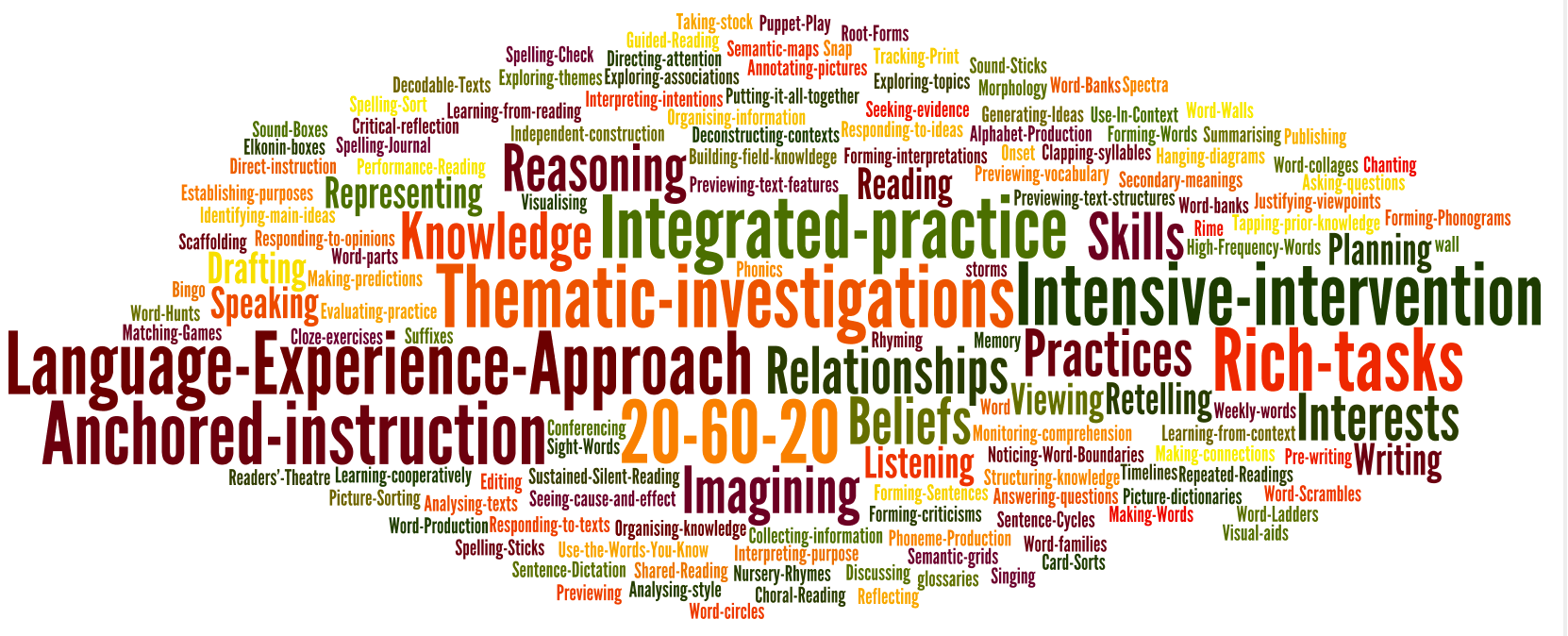

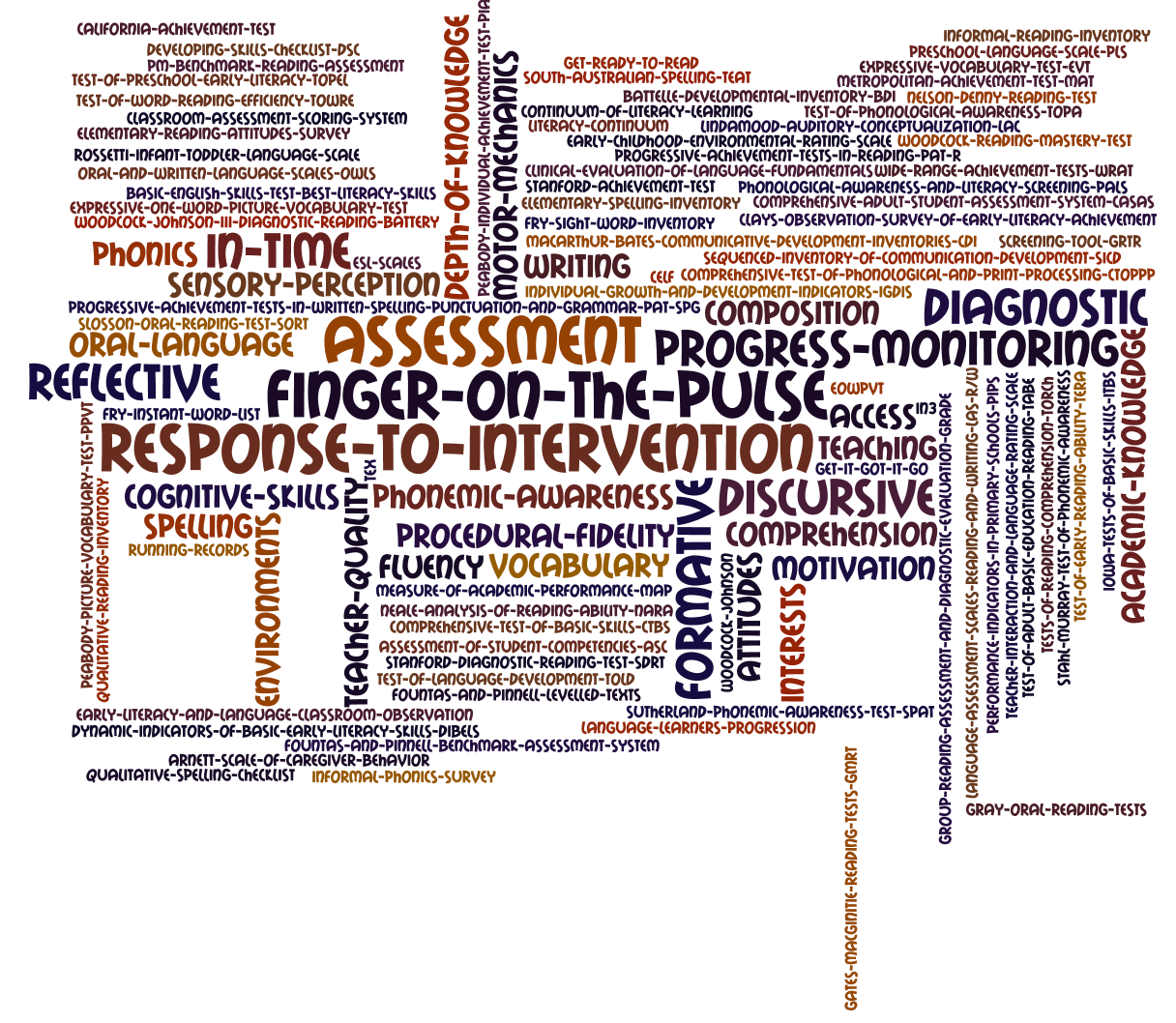

Nevertheless, exciting possibilities lay ahead. I look forward to expanding the literacy resources available on the site: links to fantastic online resource, lesson plans and ideas, great books for all ages and interests, and tips and tricks to help readers and writers as well as teachers and students. While I will miss having a little corner of the Internet carved out explicitly for the discussion of a certain application of Wittgenstein’s manner of approaching language, I couldn't honestly continue to act under the title Wittgenstein on Literacy/Learning when the conversation was moving more and more into a direct and contemporary discussion of literacy learning and instruction. So I must let the original (2007) premise of website evolve into what we have now and will have in the future.

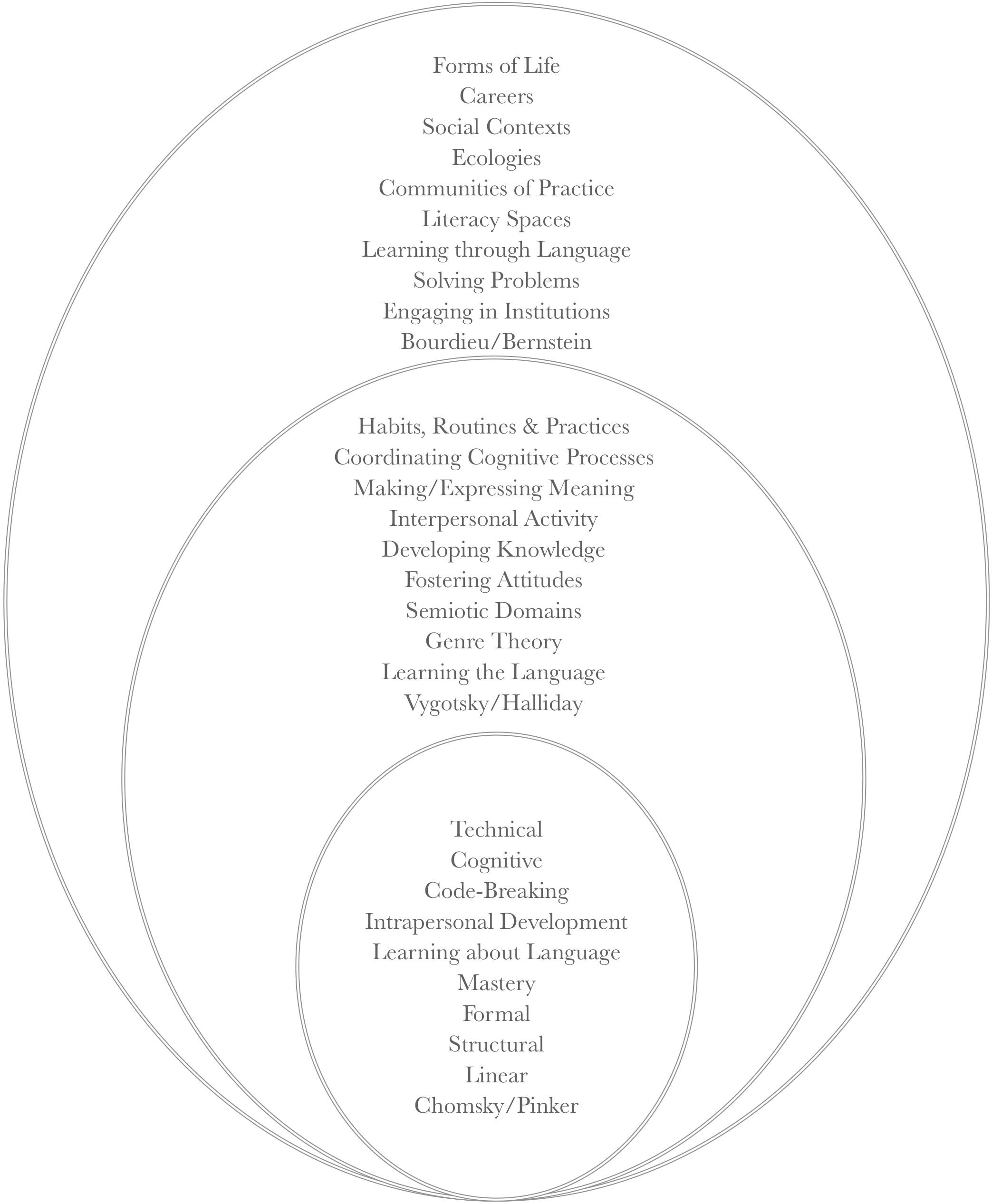

The truth of the matter is this ... I may - in fact - be allowed to be more Wittgensteinian (without feeling the need to explicitly link observations to Wittgenstein). I may be freed to discuss a range of literature (children’s, young adult and more) with a keen eye on how readers and authors co-construct meaning based on certain shared assumptions. I may be better positioned to marvel at the developmental leaps that learners make as they grow through the various stages of literacy learning. I may be better able to provoke visitors to reconsider how our environments, practices, relationships and politics influence the potential for learners to catch the literacy bug and - thereby - take charge of their intellectual journey.

In the end, literacy is wide ranging phenomenon. What it means to a two year old and a four year old is different to what it means for a ten year old, a sixteen year old, a twenty year old, a thirty-five year old, a fifty year old and more. What it means now is different than what it meant thirty years ago and what it will mean in forty years time. The shape of literacy practice in urban Chicago is different to the role it plays in remote Australia which is different to the texts, contexts and traditions encountered by present-day youth in Cairo. That said, there is the old saying ... the more thing change, the more they remain the same.

Nevertheless, I am getting well ahead of myself. Welcome to The Literacy Bug … a little creature with the capacity to fly, burrow, nest, transform, whiz about and inspire. Please visit the new home page for a fresh discussion of the road ahead and subscribe to receive regular updates. And whilst you are here, stop by the site’s many familiar places: the themed notes, the key essays, the teaching principles, the reading lists and the glossaries. Welcome! Explore and enjoy!